This article was originally published in Quanta Magazine.

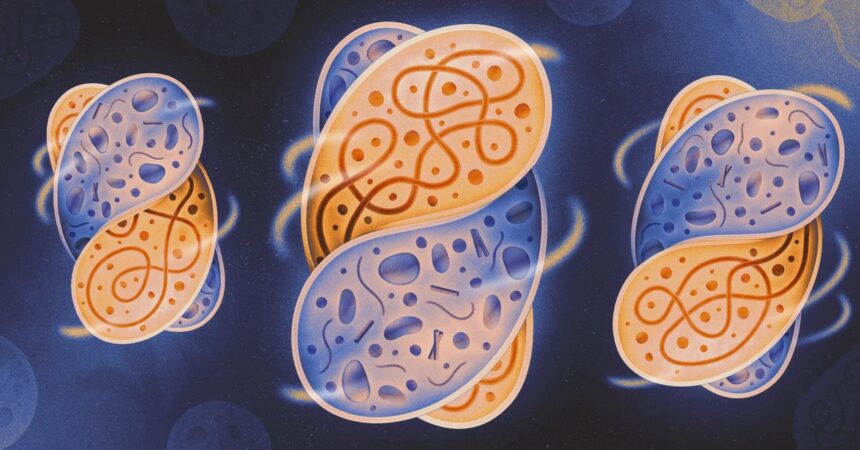

Contrary to the notion of operating in isolation, most single-celled microbes engage in intricate interactions. Whether in oceans, soils, or within the human gut, these microorganisms may engage in battles, consume one another, exchange genetic material, vie for resources, or utilize the waste products of their fellow microbes. In some cases, their relationships become even more profound, with one cell infiltrating another and establishing itself. If conditions align favorably, it might become a resident, initiating a partnership that can endure for generations—or even billions of years. This process of one cell residing within another is known as endosymbiosis and has been pivotal in the evolution of complex life forms.

Instances of endosymbiosis are abundant. Mitochondria, the powerhouses within your cells, originated as free-living bacteria. Plants that perform photosynthesis derive their carbohydrates from chloroplasts, which were also once independent organisms. Many insects rely on bacteria living within them for crucial nutrients. Recently, researchers identified the “nitroplast,” a type of endosymbiont that assists certain algae in nitrogen processing.

Although endosymbiotic relationships are fundamental to many life forms, scientists have faced challenges in deciphering the mechanisms behind them. How does an internalized cell evade being digested? How does it learn to reproduce within its host? What transforms a random fusion of two independent organisms into a stable, enduring partnership?

Now, for the first time, scientists have observed the initial stages of this microscopic interplay by artificially inducing endosymbiosis in a laboratory setting. By injecting bacteria into a fungus—an endeavor that necessitated innovative solutions (and the use of a bicycle pump)—the researchers successfully fostered collaboration without harming either the bacteria or the host. Their findings provide insight into the conditions conducive to similar occurrences in natural ecosystems.

The cells even adapted to one another more rapidly than expected. “To me, this indicates that organisms inherently desire to coexist, and symbiosis is the default state,” remarked Vasilis Kokkoris, a mycologist specializing in the cell biology of symbiosis at VU University in Amsterdam, who was not part of the new study. “This is significant news for me and for our understanding of life.”

Despite early attempts that were unsuccessful, insights into how, why, and when organisms accept endosymbionts can lead to a deeper understanding of pivotal moments in evolutionary history, as well as the potential creation of synthetic cells enhanced with powerful endosymbionts.

The Breakthrough in Cell Walls

Julia Vorholt, a microbiologist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, has long contemplated the factors influencing endosymbiosis. Researchers in this domain have theorized that once a bacterium penetrates a host cell, the dynamics of the relationship swing precariously between infection and harmony. If the bacterium multiplies too quickly, it could exhaust the host’s resources, triggering an immune reaction and possibly causing the demise of either partner. Conversely, if replication is too slow, the bacterium risks failing to embed itself within the cell. It was believed that only in rare instances does the bacterium achieve a balanced reproductive pace. To earn the title of a true endosymbiont, it must also integrate into the host’s reproductive cycle, ensuring its passage to the next generation. Eventually, the host’s genome must adapt to accommodate the bacterium, forging a pathway for both entities to evolve as a cohesive unit.

“They become interdependent,” Vorholt explained.