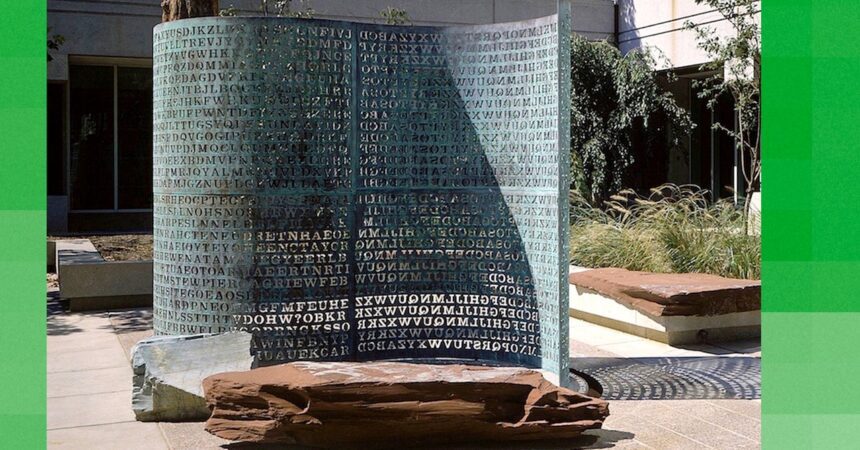

For the past 35 years, enthusiasts and professional cryptographers alike have attempted to decode Kryptos, an impressive sculpture located behind the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. In the 1990s, the CIA, NSA, and a computer scientist from the Rand Corporation each independently generated translations for three of the four panels filled with scrambled letters. However, the concluding segment, referred to as K4, was encoded using more complicated methods and continues to be unresolved. This ongoing challenge has intensified the fascination of countless aspiring codebreakers. Whenever someone believes they have cracked the code, they reach out to Jim Sanborn for verification. Sanborn is the artist behind the installation and the sole individual privy to the solution. Recently, the influx of these inquiries has surged. Sanborn, however, finds this trend rather frustrating—not for the reasons one might assume.

Take, for example, the email from one recent aspiring codebreaker. “What took 35 years, even with the NSA’s vast resources, I managed to solve in just 3 hours before I’d even had my morning coffee,” it began, before the sender presented what they thought was the elusive solution. “History’s rewritten,” claimed the writer. “No mistakes—100% cracked.” One might wonder how someone could be so convinced they had outperformed the world’s top mathematicians and cryptologists, including some who may have a quantum computer hidden away. The explanation is emblematic of 2025: a chatbot!

It appears that the latest generation of AI models is readily accepting prompts aimed at deciphering Kryptos, effortlessly producing a decoded message in plain text and claiming success. Sanborn reports that he is encountering this phenomenon more frequently. Naturally, the submitted “solution” was completely incorrect, just like the countless others he had previously dismissed.

Sanborn recently reached out to convey his frustration with this situation. “It feels like a significant change,” he states. “The volume of submissions has increased dramatically. And the tone of the emails is different—the individuals who used AI to crack the code are utterly convinced that they’ve solved Kryptos over breakfast! AI seems to be deceiving them, assuring every one of them that it’s 99.99% certain they’ve cracked Kryptos, congratulations. So by the time they contact me, they are thoroughly convinced they have succeeded.”

This trend unsettles Sanborn for various reasons. Until recently, there existed an unspoken understanding among the artist and the devoted crypto enthusiasts that the quest to decode the message would be approached earnestly. (Years ago, Sanborn began charging $50 for solutions, creating a hurdle to filter out outlandish guesses and eccentric submitters.) This exchange enriched the artistic essence of Kryptos; having an object that resists resolution set against the backdrop of the CIA serves as a subversive commentary on the nature of intelligence gathering, where every truth is subject to scrutiny. The extensive effort exerted by thousands to uncover the plaintext—suggesting, based on the decoded panels so far, that Sanborn’s message reflects on secrecy itself—is seemingly lost on newer participants.

“The current crowd attempting to decode Kryptos lacks understanding of what it truly is,” says Sanborn. He finds himself sorting through emails from random individuals employing AI shortcuts that demand minimal thought and expertise, not to mention a genuine appreciation for the challenge. It’s akin to claiming one has ascended Everest by helicopter, but even worse, for these novices haven’t cracked the code at all; they’ve scarcely managed to rise above sea level. Sometimes, in his responses, Sanborn isn’t shy about expressing his views. “I can tell from your assurance that you used AI,” he remarked to one misguided participant. “AI deceives and lacks adequate information.”