Nairobi, Kenya – In the afternoon of August 19, brothers Jamil and Aslam Longton had just finished lunch at home and were on their way back to work at the cybercafe they own in Kitengela town, on the outskirts of Nairobi, when they noticed someone suspicious.

A woman was hanging around outside their gate, talking on her phone, just like she had been earlier that morning when they left for work.

As they got into their car to leave, the woman, along with two men, blocked their path with several vehicles a few yards down the road. They approached the car and pulled Aslam out of the driver’s seat. The 36-year-old had been an active participant in recent anti-government protests in the country.

Despite being in plain clothes, Jamil, 42, believed that the heavily armed group that accosted them were police. This was due to a series of abductions of political dissidents in Kenya, as well as a warning he had received.

Just less than two weeks before the incident, Jamil, who is also a human rights activist, received a call from a high-ranking security official in the area. The official instructed him to warn his brother to steer clear of protests. Otherwise, “they might harm him”, the caller threatened.

As the armed men forcefully removed Aslam from the car that day and shoved him into their waiting SUV, Jamil protested, demanding proof of their identity and questioning the legality of the arrest.

When they refused to answer, Jamil threatened to contact the local police station. “Noticing my resolve, they also grabbed me and forced me into the vehicle, blindfolded us, and drove us around the city in a manner that made it difficult to ascertain our location,” he recalled.

The brothers were kept in a dark room for 32 days where they were subjected to beatings and death threats if they did not disclose information about the funding of local protests in Kitengela.

“They only opened the room every 24 hours to give us a small portion of ugali [maize meal] and provided us with 500ml of water once every 24 hours, along with a small can for use as a toilet,” Jamil recounted to Al Jazeera.

Finally, the abductors blindfolded the brothers and drove them to Gachie, a small town 14km (8.7 miles) north of Nairobi, where they were abandoned. Later, they discovered that a friend who was also a protester had been abducted and released.

Such incidents have been on the rise in recent years, targeting both locals and foreigners, with the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) highlighting a “disturbing trend of abductions in various parts of our country”.

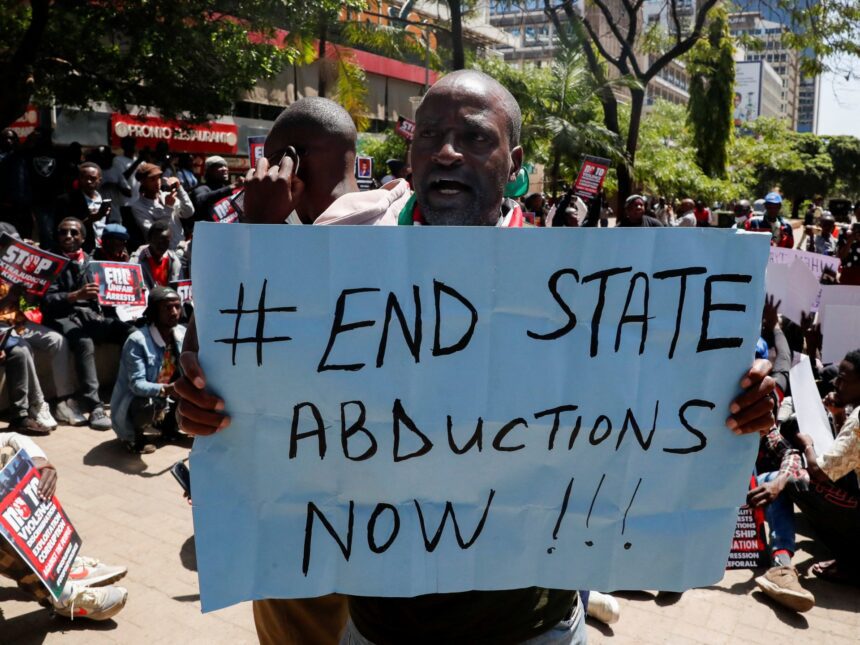

Since the youth-led protest movement against the government began in June 2024, residents and rights groups claim that abductions have increased.

There have been 82 cases of abductions and enforced disappearances since the protests started, with 29 individuals still missing, according to KNCHR. “Those abducted have been vocal dissenters,” the rights body stated.

Protesters targeted

During the 2024 protests, Kenyan youth took to the streets demanding political and economic reforms after President William Ruto introduced a controversial finance bill, which would have caused a sharp rise in the prices of basic goods. The protests were met with a brutal crackdown by security forces which resulted in dozens of casualties.

Ruto eventually withdrew the bill and the protests subsided, but many activists took their dissent online. Rights groups claim that protesters and social media activists continue to be monitored, harassed, and worse.

Human Rights Watch (HRW), which investigated the abductions, spoke with witnesses and survivors who alleged that security officers – often in plain clothes with concealed faces and driving unmarked vehicles – forcibly disappeared protesters and even eliminated some perceived protest leaders.

HRW’s research revealed that the officers involved in the abductions were from agencies of the Kenyan National Police Service, such as the Directorate of Criminal Investigations, the Anti-Terrorism Police Unit, and the National Intelligence Service.

Nevertheless, Kenya’s government and law enforcement agencies have denied any involvement in the abductions. The National Police Service did not respond to Al Jazeera’s requests via email for comments on accusations of police complicity in enforced disappearances. Police spokesperson Michael Muchiri only stated in a WhatsApp message that the police’s role is to combat all forms of criminal activity and that reported cases have been handled appropriately.

Despite initially dismissing reports of abductions in Kenya as “fake news,” President Ruto finally acknowledged the issue in December and pledged to address it. However, he did not accept government responsibility.

“We will put a stop to the abductions so that Kenyan youth can live in peace,” he declared at a stadium in Homa Bay, western Kenya. Nevertheless, he urged parents to “take responsibility” for their children, possibly alluding to youth protesters.

The previous month, Ruto had mentioned abductions in his annual state of the nation address, condemning “any excessive or extrajudicial” actions. However, he maintained that many detentions were legitimate arrests of “criminals and subversive elements”.

In a recent interview on Al Jazeera’s Head to Head, Kimani Ichung’wah, the majority leader of the Kenyan National Assembly, reiterated the government’s position that there are “criminal elements involved” in the protests, stating, “I do not believe there are enforced disappearances orchestrated by the state in Kenya, not in this day and age.”

Nevertheless, civil society organizations have criticized Ichung’wah’s previous statements on the matter, including allegedly spreading false claims that abductees are staging their own kidnappings for financial gain. The Kenya Human Rights Commission called for his resignation.

According to the State of National Security report presented to parliament by Ruto in November, Kenya had already seen a 44 percent increase in abductions between September 2023 and August 2024, with 52 abductions reported compared to 36 during the same period the previous year.

Rights groups concerned

“There’s widespread concern about the abductions. Some of the abducted individuals are turning up dead, and the state is not taking measures to prevent it or safeguard the people,” Otsieno Namwaya, East Africa director at HRW, told Al Jazeera.

“We have evidence indicating that those abducting protesters and government critics are actually state agents,” Otsieno stated. He added that peaceful gatherings have been violently disrupted by the police, and citizens speaking out about basic health and social issues are being apprehended or detained as if they had committed grave offenses.

Otsieno described the abductions as “very alarming”.

Amnesty International Kenya, in collaboration with other human rights groups and bodies, has expressed concern over the “excessive force and violence during protests” as well as the abductions.

“We have publicly called for the release of abducted individuals, organized independent postmortems, and supported legal action on habeas corpus cases that seemed to involve enforced disappearances,” stated Houghton Irungu, Executive Director of Amnesty Kenya, describing the cases of enforced disappearances and missing persons as “tragic” for the country.

“This has led to a decline in Kenya’s democratic status under the CIVICUS Global Monitor,” he told Al Jazeera, referencing the alliance of civil society organizations monitoring civic freedoms.

“State violence should not be the response to citizens’ dissatisfaction or demands for accountability and responsive governance. The Kenyan authorities must adhere to constitutionalism and international human rights law,” Irungu emphasized.

Irungu argued that failure by Kenya to uphold national and international human rights standards could impact its international reputation, including on bodies like the United Nations Human Rights Council and the African Union.

“Kenya is on a dangerous path, and it appears that the government currently does not prioritize human rights,” HRW’s Otsieno noted.

He highlighted the Kenyan abductees as indicative of this trend and also mentioned “cross-border abductions,” which he said has been a longstanding concern for HRW.

“We have seen South Sudanese individuals abducted and sent back to South Sudan where they were killed. Ethiopians have been abducted and repatriated to Ethiopia. Congolese have been taken back to Congo, and now Ugandans are being abducted in Kenya and sent back to Uganda.

“This entire operation violates Kenya’s international obligations,” Otsieno concluded.

Foreigners abducted

Maria Sarungi Tsehai, a Tanzanian journalist and human rights activist residing in Nairobi, is one of the foreigners who have been seized from the streets of Kenya.

One afternoon in January, as she was leaving a salon in an upscale area of Nairobi, she noticed a woman observing her. Sarungi hailed a ride-hailing cab, but as she entered the vehicle, two men pulled her out and forced her into a waiting van, where they blindfolded her and drove off.

Sarungi used to operate a television station in Tanzania, but after the government cracked down on independent media and other dissenting organizations, she was forced to close. She moved to Kenya in 2020 and continues her work, which includes writing on governance and political repression in Tanzania.

She believes her abduction was due to her criticism of the Tanzanian government. While she was held captive in the moving vehicle, her captors attempted to coerce her into revealing her passcodes to access the mobile phone she uses for her activism and to communicate with whistleblowers. One of her captors spoke Swahili with a Tanzanian accent.

After Sarungi was abandoned on a dimly lit street four hours later, a friend sent her a screenshot from a WhatsApp group chat where members of Tanzania’s ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party were discussing her.

“After being abducted, I received a message from the party’s WhatsApp group where a member expressed joy, essentially saying, we successfully carried out this operation,” Sarungi recounted. Screenshots of the group chat were leaked and shared by human rights activists on social media.

Sarungi is convinced that authorities in Tanzania and Kenya either participated in or were aware of her abduction. She recalls her captors stopping at what sounded like a police checkpoint during her ordeal, indicating that the police were possibly complicit. Al Jazeera reached out to both the Kenyan National Police Service and the Tanzanian police for comments on Sarungi’s abduction, but received no response.

Other foreigners have also been snatched from Kenyan streets, with some being handed over to their adversaries back in their home countries. This includes Ugandan opposition leader Kizza Besigye, whose legal team claims he was seized in Nairobi in November and returned to Kampala, where he is now incarcerated. In July, 36 members of Besigye’s party were also seized. They were arrested by Kenyan police and handed over to Ugandan authorities, subsequently facing terrorism-related charges.

‘Secret unit’

Despite authorities in Kenya continuously refuting any knowledge or involvement in enforced disappearances, certain statements from senior officials have been revealing.

In December, Kenya’s former Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua, who was impeached due to his support for the youth protests and subsequent fallout with Ruto, stated that “abducting young people is not a solution” and alleged the existence of a secret unit responsible for disappearances in the country.

“There is a unit that operates independently of the Inspector General of Police. There is a building in Nairobi, the 21st floor in the city center, where the unit operates from, led by … a relative of a very senior government official,” Gachagua revealed to reporters in December.

Then, on January 15, Justin Muturi, the Public Service Cabinet Secretary, claimed that his son Leslie Muturi was abducted during the anti-government protests last year, and alleged that his kidnapping was carried out by the National Intelligence Service (NIS).

In a statement to the Directorate of Criminal Investigations, Muturi mentioned that he had met with President Ruto after his son was taken. Ruto then contacted the NIS, after which Leslie was released.

On January 30, National Police Service Inspector General Douglas Kanja and Director of Criminal Investigations Mohammed Amin were summoned to court to explain the whereabouts of three youths – Justus Mutumwa, Martin Mwau, and Karani Muema – who were seized in mid-December in Mlolongo, just a few kilometers outside Nairobi.

Kanja informed the court that the three individuals were not in police custody and their location was unknown.

However, Mutumwa’s body was discovered at a city morgue a few hours later. Shortly after, Mwau’s body was also found at the same morgue. Muema remains missing.

Activists and human rights lawyers raised concerns about the competence of the authorities and questioned their transparency with the public.

“The Inspector General and Director of Criminal Investigations appeared in court and claimed no knowledge, yet fingerprints were taken and the bodies identified. It suggests they are either not communicating or do not have control over the different agencies within the National Police Service, or they are deceiving the Kenyan people,” said Faith Odhiambo, President of the Law Society of Kenya (LSK).

Kenyans and foreign nationals in the country are worried about their safety, with blatant abductions taking place in broad daylight. Nevertheless, when IG Kanja appeared in court in January, he reassured the public that Kenya was secure.

“Your honor, I wish to assure the people of Kenya that they are safe. The festive season just passed without any incidents, and people were able to enjoy the Christmas period because our country is safe. So, I want to reassure you that we are safe,” he stated.

Meanwhile, in Kitengela, the Longton brothers are still recovering from their ordeal of being held captive for a month. They revealed that they are now being surveilled by security agents.

Jamil, who leads a local organization called Kajiado County Human Rights Defenders, stated that despite the threats from the government, he encourages Kenyans to exercise their democratic right to protest.

“They used threats to dissuade us from participating in protests or speaking to the media because they would harm us, but that was simply a scare tactic,” he explained. “Every Kenyan, as a patriot, will exercise their constitutional right to demonstrate and protest if they are dissatisfied.”

In Nairobi, Tanzanian activist Sarungi remains shaken.

The abduction experience has made her more cautious in her daily life in Kenya, but it has not diminished her resolve to strive for a better society. She refuses to be silenced.

“If we keep quiet, that is what they want. Is there a cost to pay? Yes. Does it mean that I will no longer live freely as before? Yes. But that will not deter us from highlighting the poor governance we witness in our society.”